I’ve decided it’s time to get back to regular posts about weekend poetry reading. I’ve been doing the reading but not finding the time to mention it.

This weekend I’m re-reading the truly wonderful sequence of sonnets ‘A Bargain with the Light’, which was one of my favourite books of 2017 and also chosen by the Poetry School. It give you insights into Lee Miller’s life as well as her photographs and by the end you feel as if you know her.

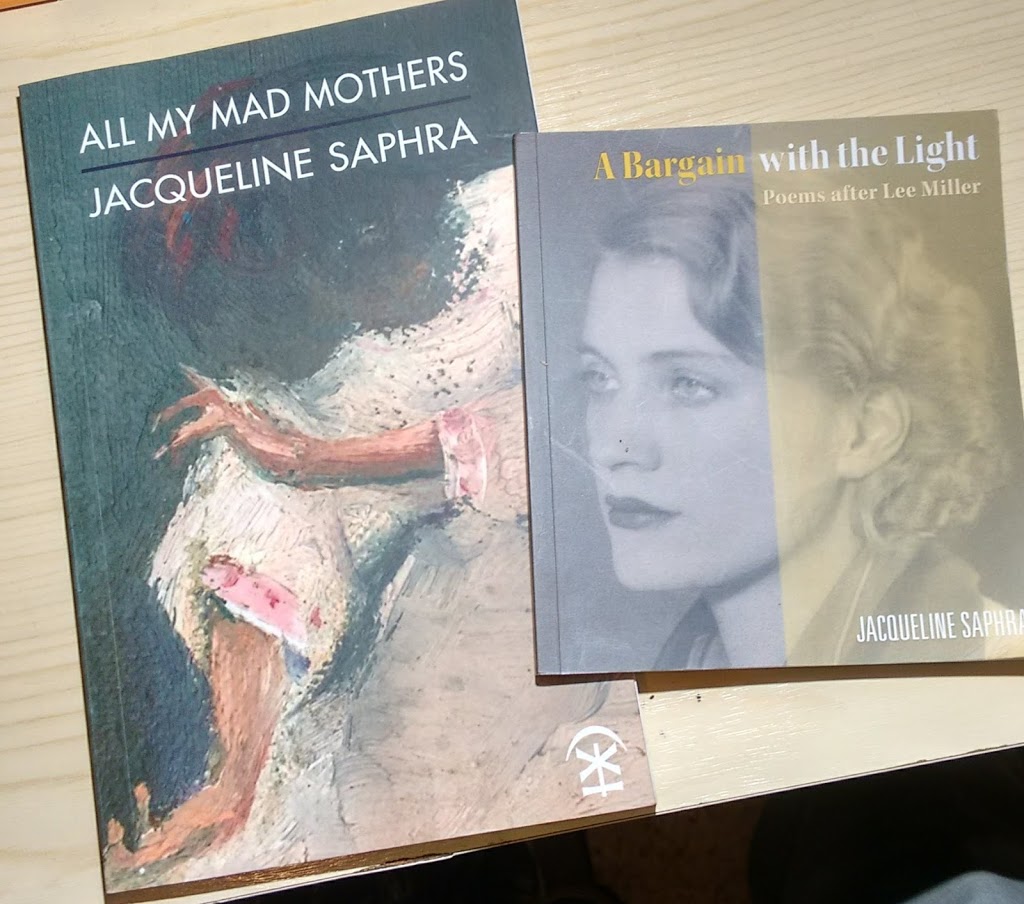

Ahead of next weekend’s T.S. Eliot Prise readings I’m engaging with All My Mad Mothers which is one of the ten short-listed collections. You can hear Jacqueline (and the other poets) talking about their work here.

‘All My Mad Mothers’

My mother gathered every yellow object she could find:

daffodils and gorgeous shawls, little pots of bile

and piles of lemons. Once we caught her with a pair

of fishnet stockings on a stick, trying to catch the sun.

My mother never travelled anywhere without her flippers,

goggles and a snorkel. She’d strip at any opportunity:

The Thames, The Serpentine, the shallows of a garden pond,

a puddle in the park. She was no judge of depth.

My mother was a dipterologist, sucking fruit flies through a straw.

Our house was filled with jars of corpses on display. Sometimes

she’d turn them out, too dead to flee, their wings still glinting,

make them into rainbow chokers, for our party bags.

My mother barely spoke between her bruises:

her low cut gown was tea-stained silk, and from behind

her Guccis or Versaces, she would serve us salty dinners,

stroke a passing cheek, or lay her head on any waiting shoulder.

My mother was an arsonist. She kept a box of matches

in her bra, lined up ranks of candles, ran her pretty fingers

through the flames. At full moon, she would drag

our beds into the garden, set them alight and howl.

My mother was a fine confectioner. We’d come upon her sponges,

softly decomposing under sweaters in a drawer, or oozing

sideways in a filing cabinet. Once, between her pearls

and emerald rings, we found a maggot gateau, iced with mould.

My mother was hard to grasp: once we found her

in a bath of extra virgin olive oil, her skin well slicked.

She’d stocked the fridge with lard and suet, butter – salted

and unsalted – to ease her way into this world. Or out of it.